Every year on this day, our collective attention in all its incarnations– TV, Print and the Internet– is littered with countless articles condemning and celebrating Mohandas Gandhi, seeking to reinterpret the long legacy of a man whose spectre looms large over the life and legend of our Republic. Most of these articles– thanks to the sheer force of simple probability– are condemned to be banal, repeating the same tropes about Gandhi’s endless laundry list of problematic beliefs as those that appeared last year and the year before that, all the way back to when the man was still alive and threatening to fast unto death. Others pick anecdotes from Gandhi’s life to paint a broader, more favorable picture of his character.

It’s all very predictable, a yearly ritual held afloat by the inertia of newspaper editors and the illusory self-importance of public intellectuals. Tomorrow, the homilies and the abuse will all cease to be and some would joke about Gandhi’s greatest contribution being a long overdue long weekend.

Yet, as I look beyond the newspapers, at the cultural laboratories of social media, the value of this yearly ritual seems no more than the price of the newspapers they appear in. Nathuram Godse is trending on Twitter, propelled by the dangerous delusion of middle-class, middle-aged men who secretly view porn during their office hours, that they are capable of humor. On Instagram, where I am mostly found, people of my generation, that don’t need to view porn secretly, have put out stories condemning the celebration of this “sexual predator, who was also a casteist and racist bigot”. Brands and celebrities have posted perfunctory digital art of round spectacles with out-of-context inspirational quotes to let the world know that they are not living under a rock.

I relate to none of it. I couldn’t care less about Godse, and I am tired of 18-year-old university freshmen that ritually rant about not being able to read more than a few sentences in a day, preaching to the rest of us about the need to constantly re-educate ourselves about our privileges. In all these instances of denouncement and celebration, there is something shockingly shallow, a laziness perhaps that masquerades as opinion.

Gandhi is a man buried so deep in history and hagiography that his life and humanity are now an inconvenient detail in the countless simplistic narratives of India’s past, present and possible futures.

But people, unlike ideas and ideologies cannot be understood merely as the function of their utility and deformities. I have always believed that understanding the great figures of history, especially those that have contributed to the birth of the modern Indian Republic, is a personal journey that is at once emotional and intellectual. So here I am, writing this meandering piece, convinced, as is everyone else about theirs, that what I have to say is somehow worth reading. At least reinventing the wheel gave us mass, portable music long before the digital revolution. We’ll see what comes out of yet another long essay on Mohandas Gandhi.

The first thing that strikes me about Gandhi is how little he truly matters to the substance of our Republic today. He played no part in the making of the constitution, choosing instead to travel to Kolkata, in the wake of the partition and force peace among Hindus and Muslims by fasting. None of his ideas of India, collected crisply in Hind Swaraj and the large body of journalism he left behind, have found any place in the words of either our constitution or its myriad critics. India is not a village Republic with deep participatory democracy. It has not so much rejected western civilization (as Gandhi wished) as it is in an unhappy marriage with it. It has not regressed to a romanticized, Rousseauian, pre-industrial past where “man lives in harmony with nature”. Gandhi’s distaste of technology is at odds with India’s most “valuable” exports today, Sundar Pichai and Satya Nadella. And that’s a good thing.

Most of Gandhi’s legacy is to be found in the everyday politics of the country– in the tradition of peaceful protests, boycotts and picketing– and in the co-option of his principles in schemes and slogans such as Swachh Bharat, Atmnanirbhar Bharat and Make in India. He is a symbol of prestige, quoted more often than he is understood, a national myth that solicits lip service from time to time, but little else.

He is taught in school textbooks, as he was taught to me, as the undisputed hero of India’s nationalist struggle. I still remember the stark contrast of the thinly-veiled Hindutva politics of the history teachers that taught me about him. Their politics meant that they’d spend much longer on the Khilafat movement than the round-table conferences or the Dandi March. Like most schoolchildren growing up in the 2000s and 2010s, a deep-rooted exasperation, distaste even, of Gandhi took hold of me. To many of us, it was perhaps a rebellion against the dogmatic deification that was shoved down our throats by our textbooks, written by authorities we couldn’t challenge. We revolted by disseminating scandalous details of Gandhi’s sex life– among them the infamous episode of him sleeping with his grandnieces to test his self-restraint. We revolted against his omnipresence in India’s modern history by downplaying his contribution to the nationalist struggle and glorifying the violent tactics of Bhagat Singh and his ilk. Then, I read The Story of My Experiments with Truth and realized that the debate over whether Gandhi was truly responsible for India’s independence was uninteresting and ultimately futile.

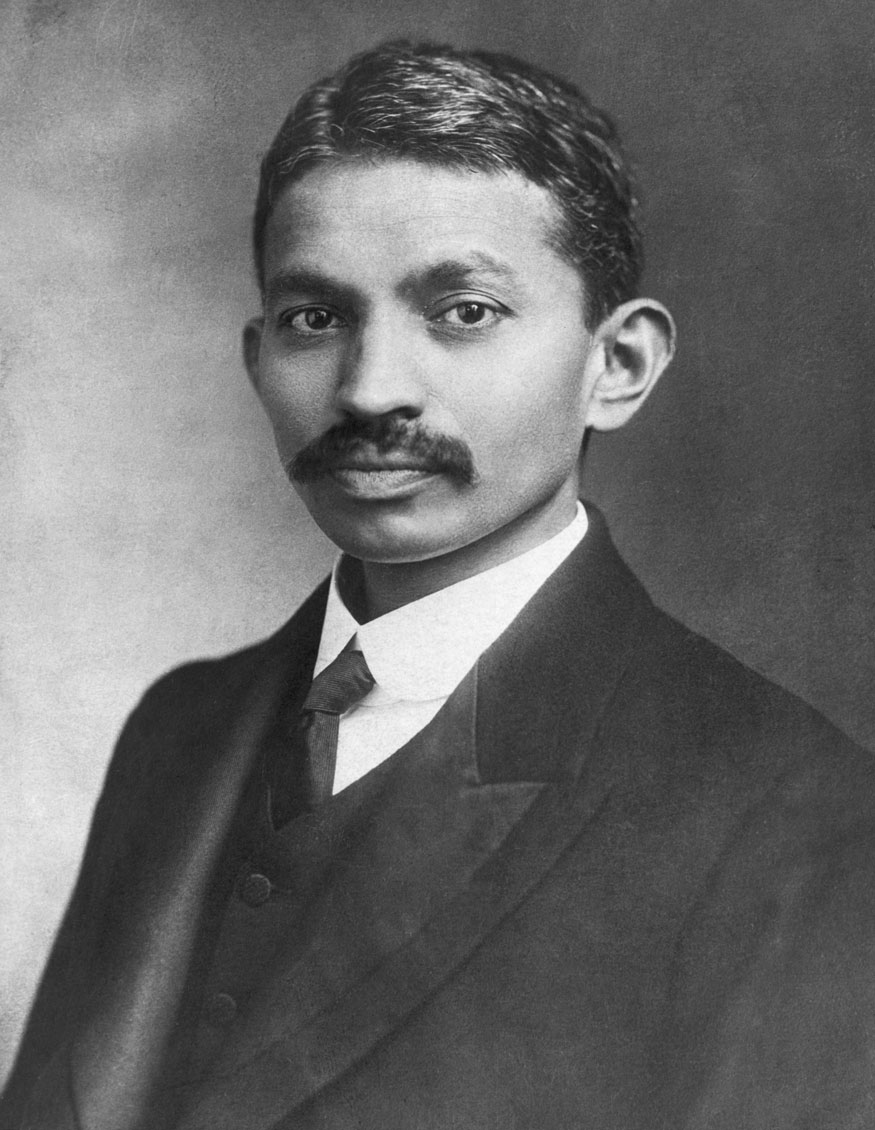

One Sunday morning in 2014, my father was clearing out his bookshelf and our house was taken hostage by industrial amounts of dust and sneezing. A mask firmly covering his nose and mouth, my father pulled out one moth-eaten book after another, their covers crumbly and discolored, their pages translucent. Most of these books had languished in far corner by our spare bedroom for the best part of twenty years. These books were in many languages– a few thin titles in Hindi, a large collection of Odia fiction and poetry, almost everything that Tagore ever wrote, untranslated, in original Bengali and some non-fiction in English. It was in the latter section that I found My Experiments. It was underwhelming to look at. One would expect the memoir of the “Father of the nation” to be look as iconic as his bald head, naked chest and round glasses.

I picked up the book and flicked through its pages, only to realize that the font was too small to permit pleasure reading. I soon downloaded a PDF file and read the book in its entirely. I was 15; much of it evaded me. But when I was done with it, I knew that the book would stay with me. I found that I could identify with Gandhi’s struggles in the book, as a teenager himself, between the many seductions of falsehood and the burden of truth, between the allure of sexual pleasure and the dry demands of duty. The memoir could have done without its claustrophobic moralism, but the visceral honesty of the lowest episodes of Gandhi’s life, like when he made love to his wife as his father lay dying was at once unsettling and touching. He was 16 then, only a year older than I was. I tried to imagine what it would mean to have sex, and what it would mean to lose my father. I couldn’t.

Newly fettered to the emergence of my sexuality, I was then having a hard time (no pun intended) understanding the change in my outlook towards life, pleasure and the female sex. The euphoric amnesia of ejaculation, the instant current of pleasure was unlike anything I had experienced before. Often, I suspected that sexual pleasure was in fact the only truth worth remembering, the best thing to have ever happened to the human race, and that everything else– school, sports and studies– were but distractions designed to keep me from being truly happy. If mere masturbation could be so logic defying, how irresistible would it be to actually make love to someone? It was simply beyond my imagination. So was the thought of losing my father. The only thing standing between destitution and middle-class comfort was my father. I had been to my father’s childhood home twice, and was struck on each instance by the sheer poverty of it. By then it had become a proper single-storey house, but not much earlier, it had been a run-down, straw-roofed, mud-baked hut, without electricity or running water. Women died young, coughing over the thick black exhaust of the coal stove. That was what I knew we’d be reduced to, if my father died.

In that moment, I felt sorry for young Mohandas. I felt sorry for his predicament, for the great tragedy of his father’s death and for the great ecstasy of sex. No 16-year-old deserves to go through that. I couldn’t begin to comprehend what it must have been to be Gandhi in that moment. But I tried to be kind. I pictured the bald, ever-smiling old man of my textbooks as a scared, guilt-ridden 16-year-old and he has remained in my imagination, despite all that I have read about him since, of his greatness and failings, a scared, fatherless 16-year-old that is yet to shave. At each moment in his long political life, from his time in South Africa to his rise to global stardom in the subcontinent, I suspect that great moral conflict, and fear, and the anticipation of shame plagued Gandhi.

A philosopher, I think, is an adult that could never bury the simple, deep questions of their childhood under the distractions of growing up. Gandhi was a philosopher. Unlike modern philosophers, he placed greater importance on personal experience and moral instincts than the simple calculus of thought experiments. His conflicting currents of thought ensured that his personal philosophy was in constant flux. Sometimes, this lead to near predatory behavior– such as forcing his grandnieces to sleep beside him– and his eccentric belief that the violence between Hindus and Muslims was the result of his own inability to control his sexual urges. But for the most part, Gandhi’s unceasing self-evaluation meant that his ideas, including those on race and black people, evolved for the better throughout his lifetime. His secularism is the perfect example of this. Gandhi was a deeply religious man, a traditionalist even. But he was also secular. Secular not in the way that westernized, agnostic intellectuals are. He was secular in a pluralistic sense; he understood that to be Indian was to be Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Parsi and Jain, all at once. His faith was a unique concoction of principles borrowed from various religions. He was convinced that religion was central to the human condition and that it was the most powerful force of moral fortitude in times of great personal and political crisis. His secularism was not at odds with a nation as deeply religious as India, but was in many ways, a rational extension of the same. It seemed obvious to him that the religious would recognize and respect the religiosity of those that chose to worship other gods, and that they would see the distinction between their gods, not as a point of division but as different articulations of the same human capacity to perpetually battle the evil within them.

All nations, as Benedict Anderson puts it, are imagined communities. And nothing comes more naturally to human imagination than stories. All nations, therefore, manufacture foundational myths that hold them together, that allow individuals with disparate lives to find common ground. Among these foundational myths, are those about the nation’s great men and women, who are sanitized and deified as heroes whose sacrifices have resulted in the privileges that the nation bestows upon its citizens. Gandhi’s is also a foundational myth, and like all myths, it is rather simplistic, and thereby vulnerable to being challenged.

If the maturity of a democracy is measured by whether its citizens are free to challenge its national myths, India can be considered a mature democracy in at least this one regard: It is not only easy to criticize Gandhi, but it is also fashionable to do so. No matter where one dwells in the political spectrum, they can find something to hate about Gandhi. And that means nothing more than the fact that the myth of Gandhi is now being humanized, in all its complexity, like it deserves to be. All myths require reinvention. And it is about time Gandhi was reinvented.

Having said that, we should be thankful that it wasn’t Gandhi but Ambedkar and Nehru whose ideas of India are enshrined in our constitution. We should recognize Gandhi’s many eccentric, often dangerous ideas about development, women, dalits and modern medicine. Being a brahmin man, it is perhaps easy for me to excuse his misogyny and casteism by citing that he was a product of his times, by claiming that no man can be expected to be perfect and that all great humans of history will fail the test of unproblematic purity by today’s moral standards.

But isn’t the ability to pick and choose, the greatest privilege of having survived history? To pick and choose what we celebrate, what we care about and what we condemn. This ability to pick and choose has lead to our greatest failures, to our most damning political and moral disasters, from Hitler’s Germany to Stalin’s USSR. Picking and choosing are at the heart of fascism and authoritarianism, but they also provide us the ability to decide what to remember, to recognize complexity, to remember that history isn’t an abstraction but is indeed the sum total of the moral conflicts of individual humans that enacted it. We must not pick and choose the way CBSE textbooks and the INC do, to deify him, and we must not pick and choose the way the Hindu right and the progressive left do, to demonize him. We must pick and choose those ideas of his, those aspects of his character that are worth cherishing and recognize the ones that are better discarded.

Quite frankly, most of Gandhi’s social, economic or political ideas are unfit for current use. It is his ideas at the individual level, of integrity and honesty, of believing in something deeply, of the possibility of being a powerful politician without moral corruption, that deserve to be cherished. Gandhi recognized the power of populism, and mass sentiment. He allowed for populism when he found it necessary, like in the Khilafat movement, while also recognizing when to put a stop to it. He understood the great power of principle and integrity, the great power that a politician wields when they are at the helm of a mass movement and the responsibility they owe to the people to call the movement off at the height of its powers if the principles have been compromised. And that is something politicians and protestors would do well to remember today. For far too long idealism and principled belief have been excused in favour of inertia and vested interests masquerading as pragmatism.

We must pick and choose to learn from Gandhi’s acute self awareness, his ability to recognize his own failings, to be honest about them, and to apologize for them without flagellating oneself. It is telling that the foremost source of the criticisms leveled against Gandhi is his own large body of written work. And that is truly why Gandhi deserves to be celebrated, criticized and above all, comprehended in these times of uncertainty and moral panic. Afterall, like all dead men and women, Gandhi is what we choose to make of him.

Written so well! Absolutely true, absolutely necessary.

LikeLike